My childhood clothes resembled the old Catskills joke about food: The food is terrible at this hotel—and the portions are way too small! My mother brought my sister and me to John’s Bargain Store for our clothes. Our clothes were ugly, and we didn’t have enough of them.

Having a fashion sense is no easy task for me—which is confusing considering that my mother valued beauty and being a fashion plate above all else. She always left the house perfectly coiffed and dressed beautifully. Things matching were important to her.

Seamstresses occasionally custom-made clothes to fit her quite perfect body—even during her years as a single mother working secretary. We lived in a small dingy Brooklyn apartment, but her closet screamed, look at me!

Like most women of the early sixties, she went to the beauty parlor once a week, baking under hairdryers until she reached perfection.

Buying my clothes

By the time I was twelve (when I began earning money from babysitting money), all clothing purchases (money + choice + store) fell on me. I had no clue how or where to shop (especially with a budget limited to what I could earn on Friday and Saturday nights.) I only made it through by borrowing (stealing) my sister’s and mother’s clothes.

(Till she died, my mother stewed about the Danskin top that I stained and then lied about—I’d thrown it out.)

My fortune grew at fourteen when I began working as a supermarket cashier at Brooklyn’s Big Apple Market. I haunted the Nostrand Avenue shops near our new home; my wardrobe expanded. I found my first mini-skirt (which my mother forced me to return—within two years, she wore shorter ones) and my beloved white bell bottoms.

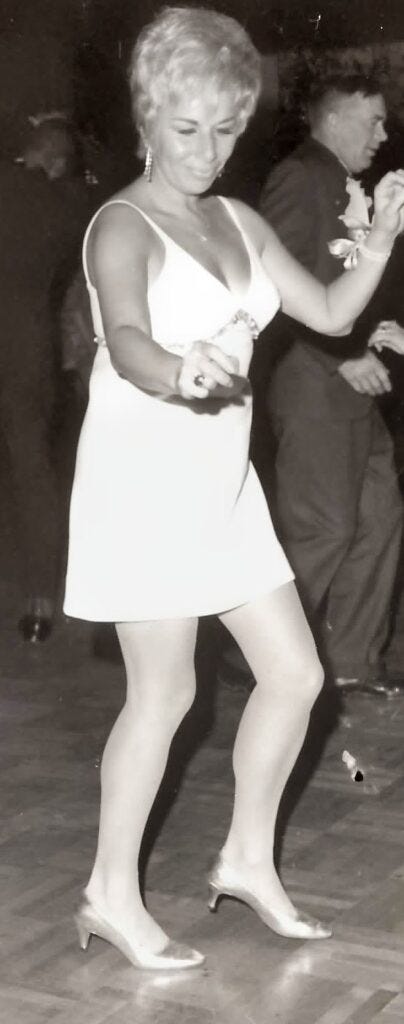

Mom hitting the disco, having decided minis were just her style after all.

At fourteen, my mother bought me a dress for my cousin’s bar mitzvah. My memory must be faulty because I remember no other clothing purchased by my mother that thrilled me. For the second time in my life (see further below for the first time—the black velvet dress from heaven., I felt special.

I lusted for clothes

I lusted for clothes because my mother’s stunning clothes knocked me out, ranging from swirling dresses for dancing to big occasion gowns. (Oddly enough, in Brooklyn, these occasions—weddings, etc., were called ‘affairs.’)

I studied pre-my-birth pictures of my mother and aunts; these photos marked me for acquisitiveness. (Later, I learned my mother, aunt, and friends bought expensive clothes, tucked in the tags, and returned them the next day.)

I saw photos like the ones below. Though someone snapped them on the prosaic Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn and the rooftop of my grandparents’ tiny one-bedroom Brooklyn rental off Flatbush Avenue, clothes from that era marked my vision of glamour.

To this day, I can’t pull off a fraction of their glamour. I can look sweet or pleasant, but smoldering and stunning are outside my realm. Still, my need for trying led me to comb thrift stores at seventeen—looking for what we now call vintage. My first purchase, which burned into my brain, was a floral nightgown I wore as a dress. I truly believed I looked exquisite in my 70’s version of affordable chic.

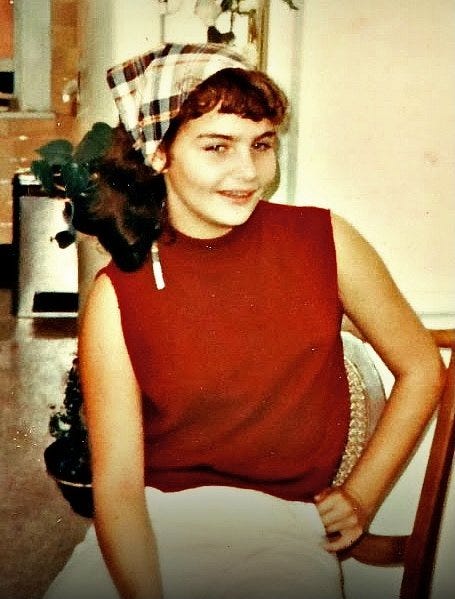

My mother kept asking why I walked around in schmattas. (below, an example of a schmatta on my head).

My only saving grace is that no pictures exist from the year of schlepping around Manhattan (I was a student at City College of New York) in the nightgown.

A few years later, married (at 19) and living in Boston, I bought a cranberry forties-era suit from Goodwill in Boston. Paired with my black wedges, I thought I rivaled Betty Grable.

My vintage black crepe forties dress followed (the one with the sweetheart neckline—ah, I remember it well) that my daughter later wore to her high school prom. She looked stunning. Both my daughters pulled off the effortless fashion looks for which I’d strived. Is it all in the genes, and my mother’s skipped a generation?

My daughters—early vintage fashion adopters—dressed up by my mother.

Touchstone Clothes

The touchstone clothes of our early years stay with us forever. I remember my five easy pieces. The nightgown-turned-dress, the 40’s look, and number three: an Afghan coat. They were incredibly popular with the coolest crowd when I was in high school. I saved up months of babysitting money, went to Greenwich Village, and bought one. Every time I wore the coat, I felt as beautiful as my mother’s Ocean Parkway picture.

Number four: a black fur (real) fox-collared coat. I won’t say from which store; who knows what the statute of limitation might be. (Reader, I shoplifted it. My mother believed me when I said I saved my babysitting money.

Number five was the black velvet dress bought by my great-uncle (the wealthiest person in our extended family) and his wife when I was six. My mother gasped when I opened the box, whispering, “That’s from Lord and Taylor’s!” She said this as though it came from the moon. I felt like a princess.

Sometimes, life needs only one magic piece from Lord and Taylor to make all the difference.

When I co-authored the novel The Fashion Orphans, I knew my character’s discomfort. I easily entered my character’s heads, women who worked hard to match their mother’s seemingly effortless magnificence, when I remembered wearing thick cotton tee shirts from John’s Bargain Store,

And I remembered turning into a princess wearing my magical velvet dress.

Memories of my five easy pieces brought the taste of feeling beautiful through clothes.

Writing that novel, I recognized how genuinely representational fashion is for women. In the words of one of the oldest characters, one who schools the younger women (women in their forties and fifties):

“For centuries, men created the rules. Wielded the power. But no matter how oppressed and repressed women have been, we’ve used clothes and accessories to express ourselves. We wore white dresses during the suffrage movement and donned amethyst, peridot rings, and brooches to proclaim our independence. We thought nothing of turning a dress inside out and re-sewing it late into the night so our daughters weren’t embarrassed to wear hand-me-downs. We refused to give up what made us feel feminine and drew seams on the back of our legs during World War Two when we had to sacrifice silk stockings for the war effort. Fashion isn’t frivolous—well, it can be—but it also is our armor.”

Only now, realizing my clothes are my protectants, can I truly enjoy them and weave my own ‘fashion sense.’ I can figure out what makes me look like a block, what gives me a pretense of shape, and what flatters me without feeling that I’m shallow.

Covering my body is non-negotiable, so why not enjoy the feel?

Have I turned into my mother—never leaving the house without matching, a soupcon of eyeliner, and a hat and sunglasses on bad hair/face days?

I prefer to think I’ve finally inherited my mother’s best traits. And, look above. I match!