How many writers come up without help? None, I’d venture to guess. Most writers can point to someone who made the difference for them—whether it was as a long-term teacher, a workshop leader, or perhaps, as a role-model of great prose. (Jenna Blum, brilliant writer and teacher, played all those roles for me.)

Elizabeth Benedict is one of my favorite authors, and also one of the most multi-talented of writers. She is the author of five novels, including the bestseller Almost, and the National Book Award finalist, Slow Dancing, as well as The Joy of Writing Sex: A Guide for Fiction Writers.  A few years ago she asked a few dozen of the best fiction writers around – including Joyce Carol Oates, Jane Smiley, Michael Cunningham, and ZZ Packer – who and what most influenced their lives as writers. The results are 30 celebrated essays on influences from Susan Sontag to Virginia Woolf, from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to Harriet the Spy, and from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop to a job running an after-school program in Harlem.

I asked Elizabeth is I could put the opening of her collection here—in the hope that others will have the pleasure of discovering this wonderful book. Enjoy:

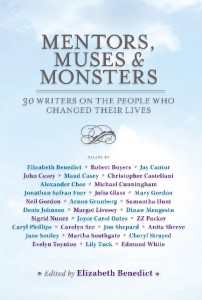

Mentors, Muses & Monsters by Elizabeth Benedict

Introduction

The response to my invitation was overwhelming.  One after another, in emails, on the phone, and in person, in a matter of weeks, dozens of fiction writers said Yes, they wanted to contribute to this anthology.  Some days I would hear from two or three or four people, saying Yes, count me in.  Of course, I was delighted – and slightly flabbergasted by the wellspring of enthusiasm.  I seemed to have hit a nerve.

Several knew right away whom they wanted to write about – Mary Gordon on Elizabeth Hardwick and Janice Thaddeus, Jay Cantor on Bernard Malamud, Lily Tuck on Gordon Lish, Jim Shepard on John Hawkes – but quite a few said yes, emphatically, without knowing their subject for sure.  Early on, Jonathan Safran Foer was deciding from among Joyce Carol Oates, with whom he studied at Princeton, the artist Joseph Cornell, whose famous boxes enchanted him at a young age, and the Israeli poet, Yehuda Amichi.  Early on, Margot Livesey wasn’t sure whether to choose her adopted father – an English teacher at a Scottish boarding school – or a long dead muse.

In saying Yes before they had settled on a subject, I picked up in writers’ voices and in their emails a yearning to acknowledge and to thank the people who had made a landmark difference in their lives – to recognize them the best way a fiction writer can, by telling the story of their association.  Because most of these encounters occurred when the writers were young and vulnerable – uncertain about their identities and what they were capable of – some of the pieces have a sweetly aching quality, and nearly all of them express abiding gratitude.  But sweetly aching or not, a good many of the writers are looking back at themselves at a tender age when something powerful happened to them, a moment when an authority figure saw talent in them, or when they came to believe they possessed it themselves – and their wobbly lives changed direction and velocity.  They knew, in a way they hadn’t before, where they were headed – and what is more potent, and more moving, than that?  It’s like being rescued.  No, it is being rescued – from uncertainty, indecision, mediocrity.

Life brings us emotional experiences to compete with that one in intensity, but the others invariably involve romance, children, family ties, two-sided associations that inevitably become messy, fraught, downright  imperfect.  But the feelings of gratitude a student or supplicant usually has for a mentor have an aura of purity about them – uncluttered, unalloyed gratitude – that’s absent from most other intense relationships.  It’s fitting that we idealize our mentors.  They are more accomplished than we are; they are in a position to bestow feelings of worth on us that carry more weight in the real world than praise from even the most ardent parents.  Their praise counts for something out there – and because of that, it also counts in here, where we live and work and proceed with nothing but whatever talent we possess, whatever nerve we can summon, and the knowledge that the only way to get to Carnegie Hall, or its literary equivalents, is practice, practice, practice – which is to say, write, rewrite, rewrite.

Mentors are our role models, our own private celebrities, people we emulate, fall in love with, and sometimes stalk – by reading their books compulsively.  In her essay on Alice Munro, Cheryl Strayed writes, “I love Alice Munro, I took to saying, the way I did about any number of people I didn’t know whose writing I admired, meaning, of course, that I loved her books…. But I loved her too, in a way that felt slightly ridiculous even to me.†When things go well, we are the beneficiaries of our mentors’ best selves, not just their admirable writing but the prescient insights that divine talent in us before we know it’s there ourselves.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jXc-7LvN8v4