“But it really happened.”

I was in an adult-ed writer’s group when I first heard this. I’d watched the woman speaking become tenser and grimmer as members of the group—gently and with compassion—suggested that the gruesome events on the page could be presented in a manner more conducive to engaging the reader.

She listened for only a few moments—sadly, this group did not have a ‘be silent while being critiqued’ policy—before unleashing, accusing the group of everything from indifference about sexual assault on children, to ignorance about how children really thought (this in response to our collective idea that 4-year-olds did not speak like 30-year-olds.) She shook as she lectured us on the horror of incest.

True that. Everything she said about her pain and suffering was true—but it still didn’t work on the page. My social services hat went on and I reacted to her effort at self-therapy on paper, attempting to bandage her up. Writing this way isn’t always a bad thing, but it’s not always good either—for the writer or the reader.

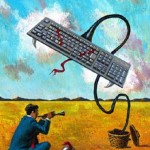

Writer X didn’t have the dramatic distance needed to make her story into fiction. Her devotion to her memories (as she remembered them) transformed her work into something uncomfortable to read, not because of discomfort with the subject matter (as she’d accused us) but because somehow her “facts” made for poor fiction.

Recently, in a moment of bravery, I looked back on my awful first attempt at a novel (where I’d mashed-up fact and fiction.) I analyzed it, curious to unearth the reasons my early work was a disaster. Reading through spread fingers in front of my face, I found that I’d worked too hard to make the me-disguised-as-a-character seem heroic, victimized, wry, adorable, etc, and the antagonists (usually ex-partners) appear as a worse or better version of who they really were. All this was done in service of revving up history, with a goal of making life unfold and then climax in the manner I’d always wanted. While perhaps good for my mental health, these goals didn’t meet the mission of providing a quality experience for the reader.

Now I believe in only using the emotional truths and themes; ‘it really happened’ events are only used as stepping-stones to the drama of “what if.” For instance, I blew up an event in my childhood, when my father attacked my mother, into a novel of a father killing his wife in front of his daughters.

Avoiding family facts while building a fictional world (orphanages, fathers in prison, foster families, medical school . . .) allowed me the freedom to present my point of view and side characters without feeling boxed in or constrained, whereas using autobiographical characters provokes my reticence. It also let me explore the theme of family loyalty in a far more dramatic and open fashion than using my own life would allow.

In my current work-in-progress, where infidelity ripples through many families and generations, I again use emotional facts while avoiding real history. Invention frees me, while following real life freezes my fiction into a boring rigidity of event telling and avoidance (hey, my family’s gonna read it!)

Even when using emotional truth, I will pick and choose what to delve into. I find that only the passion of something far enough away from my current circumstances gives me story-telling breathing room. For instance, I couldn’t write about the new-love-sex-is-amazing and life-is-Technicolor period of early relationships while in the throes of that glitter-time, for fear of sounding like the blathering idiot one does become during this time.

Other bits of life, even emotional life, I can never explore (for fear of rendering truths that are not mine to expose) are those of my children or husband. It was impossible to borrow from my mother or father’s lives until they were gone. My sister and I discussed how far I could and would go in my fiction.

I’d don’t want to be in a face-off between loyalty to a reader and loyalty to my family, so I stick with the inner and outer world that belongs to me.

It’s funny, readers so often wonder if “it really happened.” They are sometimes determined to conflate the author and the writer. A friend recently told a story of going to a book club for her novel and being told with great surprise: “You look nothing like your character!”

It is true that many love writing their life into their novels and there is room for all in the big book tent. Each of us finds our own balance, but when I write, the scenes that truly transport me and send me soaring are the furthest things from real life, but not furthest from my imagination.