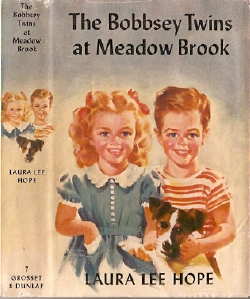

I suppose they were meant to teach me reading skills. And the goodness of clean living. But what The Bobbsey Twins taught me was needle sharp envy.

Freddie and Flossie Bobbsey’s adventures are the first books I remember reading. Their stories educated me about a world from which I was deeply, meanly, forever locked out. A blonde, blue-eyed, two-parented, petticoated, grass-to-run-on, toys-and-pets world. A life where sisters didn’t chop off your only dolls’ hair. Most certainly a life where men didn’t try to touch you.

The Bobbsey family lived in the large town of Lakeport, situated at the head of Lake Metoka, a clear and beautiful sheet of water upon which the twins loved to go boating. Mr. Richard Bobbsey was a lumber merchant, with a large yard and docks on the lake shore, and a saw and planing mill close by. The house was a quarter of a mile away, on a fashionable street and had a small but nice garden around it, and a barn in the rear, in which the children loved at times to play.

A barn? They had a goddamn barn where they could play? We had a patch of dirt in the alley, which a recent trip back to the old country (Brooklyn) showed to be approximately 2 feet by four feet. Not even big enough for a casket.

I learned to read early. Books and candy were my first drugs. My memories of reading The Bobbsey Twins brings back the first taste of pressing my face against a world I desperately wanted, and yet could believe in no more than I believed in Santa Claus. Perhaps it gave me a thirst for upward mobility; perhaps it made me feel the perpetual outsider. It certainly cooked up a stew of personal anomie that lasted a lifetime—one I still fight, convinced that there is a Bobbsey Twins way of life out there and I am missing out on it. They may be my ground zero for my preferring dark books, where I can choose a Schadenfreude, there-but-for-the-grace-of-god spirit instead of being perpetually stuck in a jealous life.

Looking back at the books, if the messages messed me up, Jewish girl from Brooklyn, destined (from an overage of Holocaust books read too early) to watch for incipient Nazis her entire life, I can only imagine what image problems the twins stories invoked for the black kids in my school, with their role model being Dinah the cook, who apparently lived her life through the shine of the Bobbsey house:

Dinah, the cook, came in from the kitchen. “Well, I declar’ to gracious!” she exclaimed. “If yo’ chillun ain’t gone an’ mussed up de floah ag’in!”

“Bert broke my boiler!” said Freddie, and began to cry.

“Oh, never mind, Freddie, there are plenty of others in the cellar,” declared Nan. “It was an accident, Dinah,” she added, to the cook.

“Eberyt’ing in dis house wot happens is an accident,” grumbled the cook, and went off to get the dust-pan and broom.

As I burrow deep into my middle age, I can let go of resenting the privilege of imaginary twins living in the land of plenty. Maybe there are real Bobbsey twins out there, in both the six-year-old and sixty-year-old versions (Flossie wearing strands of pearls, Freddie shod in Topsiders,) and perhaps they are indeed sailing their way through life on that boat on Lake Mekota. Or possibly Flossie is on her third husband, but still hungry for love and Freddie spends his nights working through a pitcher of martinis.

Either way, it’s certainly time for me to stop begrudging them whatever road they took out of Lakeport. And if they stayed in town, still nestled in the heart of their twin-setted family, happy forever, still pulling the lever for the Republican ticket, then I don’t want to deny them theirs. As long as they don’t knock what’s mine.

And they take Dinah out of the damn kitchen.

(On the steps in Brooklyn–they redid the entrance!)