“I’m looking for possible blurbs to be published on the back or inside cover of my 90-year-old mother’s novel,” Michelle Hoover wrote on Facebook. “Her health is precarious, she’s isolated in a care facility in Iowa, and I want to do something that raises her spirits and makes true one of her dreams, or as close to possible as I can. I’m trying to self-publish the book quickly— the book will be hardcover and look very good. Blurbs aren’t necessary, but God, she’d love to see them.

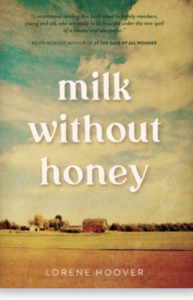

“It’s also a great book, spare, sweet, fascinating in time and place, nearly auto-fiction, and only about 200 pages. It takes place in rural Iowa during the Depression, told by a young girl whose family loses their farm and whose parents are on the verge of divorce. The mother of four attempts an escape on her own with the children to the “city” by opening her own boarding house, only to be driven back by poverty. This is a fast read. My ridiculous ask: for blurbers to get back to me, if possible, in a week.”

When I wrote “happy to help,” to Michelle, I praised myself for my sacrifice. I imagined reading the novel as one might approach a class assignment, sighing as I read enough each day to make it to the upcoming deadline.

Instead, the moment I finished the book, I emailed Michelle:

“Thank you, thank you, thank you, and many thanks to your mother for allowing me to read “Milk Without Honey.” I’d expected to read it in stolen snatches (before, I thought, switching to my current take-me-away bedtime novel) MILK WITHOUT HONEY hooked, grabbed, and immersed me.

Your mother’s book became my take-me-away bedtime novel, one I couldn’t wait to return to each night until finally, your mother shredded me on the last page; I wanted to keep reading the words of Lorene Hoover forever.

So, as I guess you can tell, readers, I loved Milk Without Honey”not in any ‘doing a good deed’ way, but in the manner of true love and then wrote a blurb that I hope captured, even a bit, how deeply I felt.

In “Milk Without Honey” author Lorene Hoover’s young storyteller, the ever-vigilant Ruth Ann, opens a secret door to Iowa during the Great Depression and leads us through this world with clarity, heart, razor-sharp observation and with the ‘gotta-know’ infused on every page. Rarely does a novel let us observe a very particular world smack through the eyes of the storyteller, but Hoover performs this miracle. I loved this book and will recommend it with the same proselytizing vigor I previously reserved for my all-time favorite book, one to which Milk Without Honey is a sister—A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.

Milk Without Honey is a book to buy for yourself, your sister, your best friend, your daughter, and please, please, please, to choose for your book club. And if they have a heart and love to read, buy it for the men in your life. Today.

And to learn how this book came to fruition, when the author, Lorene Hoover, had already turned 90, read the words that daughter Michelle wrote as a ‘publishers’ note’ (Michelle Hoover is an award-winning novelist of note, whose books are magnificent). Much like Milk Without Honey, Michelle’s words brought tears and wonder with their aching loveliness.

Publisher Note for Milk Without Honey

by Michelle Hoover

At the time of this writing, we are nearing the end of 2020 and my 90-year-old mother has been moved to a health care facility in Ames, Iowa, within Northcrest’s larger retirement community where she has lived happily and independently for decades.

This is during the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, and because retirement communities have suffered extensively from the disease, we’re not allowed to visit her more than once a week for fifteen minutes at a time, masked and outdoors in 20-degree weather, which for my diminutive mother is more bother than not. When I call her on the phone or attempt a video chat, she is more talkative than she has ever been, though at times troubled and in pain. After a recent bout of chemotherapy, she is in remission, but the medication caused memory loss, and she has fallen three times. She now suffers a compression fracture in her back and a broken wrist, and she has no idea how these things happened. Her nurses report that she is noncompliant, stubbornly insisting on doing things for herself, and because my family tends to crack jokes during stressful spells, we speak with pride about our tiny, noncompliant mother. Well under five-feet tall and weighing a little over 100 pounds, she subsists on vanilla ice cream and bad television. She is too tired to read. In her current situation, she wonders aloud what is real and what is not, musing that she has become the protagonist of her own story, though she is unsure what that story is.

Milk Without Honey is a novel, but one that follows the current trend in autobiographical fiction, though the first drafts of this book predate the growing popularity of that genre by decades. There are many differences between the novel and the historical record, but one of the biggest is that my grandmother left her husband to launch those boarding houses not with four children but with five. I’ve always marveled at how gutsy such a decision was for a woman of her time, but according to my mother, my grandmother regretted it, referring to the move to Centerville as the worst mistake I ever made. I can’t help but think it’s more complicated than that. What if she had been able to make a go of it? If the country hadn’t been mired in economic collapse, might she have had better luck? And if she did still return to her husband, what if she’d been able to do so under her own terms?

My grandparents remained married fairly happily I believe, until my grandfather died in 1972, a few months before I was born. Though I never knew him, I learned he was a great storyteller, easy in his manner, kind, and musically gifted. In another era, he too might have had different options.

I knew my grandmother as a shy, quiet woman who played the piano, could craft anything she set her mind to, stuffed me with her homemade brownies as well as a delectably simple potato mash, and derided my beloved Wizard of Oz because it wasn’t real. To my delight, she often giggled like a young girl as I babbled to her stories about my life. One bedroom of her house was taken up entirely by dozens of antique dolls, and I often snuck upstairs to scare myself silly with a glimpse of their cracked, glassy-eyed faces staring back.

Late in her life, her children were forced to move her from this house where she had lived for decades because it had become too dangerous for her to stay there alone. Her new apartment was closer to friends and medical help, but she was miserable. I remember that apartment as an impossible maze of handmade rag rugs and half a dozen enormous reclining chairs. My grandmother died soon after at the age of ninety-two. Knowing how often she was forced to move in her early married life and how desperately she tried to make a home, it’s no wonder she stubbornly held onto that house and all the furniture she could. Moving again must have broken her heart.

Sometimes now when my mother reads the medical reports about her condition, she tells me she imagines she is reading these reports about her own mother.

A nurse at her retirement community recently offered this advice: At this stage, you and your mother might have to make a terrible choice: Either she lives in a place where she is unsafe and happy, or unhappy and safe.

My mother began to write after the death of my father in 1987. She joined writing groups near Fountain Hills, Arizona, where she wintered in her widowhood, as well as in Ames, performing her work in front of audiences, trying out new ideas, new forms of expression. She returned often to the Green Lake Writers Conference, the Iowa Summer Writing Festival, and the Desert Nights Rising Stars Writers Conference, among others. Her writing community quickly became a lifeline for her, as my own has become for me.

My mother has always championed my work. She sent countless postcards and phoned family members and friends to attend my readings and buy my books. Every now and then in an unfamiliar city, a woman might appear at one of my bookstore events who seems to know me. She explains that my mother sent her. My mother has many such friends. When my first book received an embarrassing review in the New York Times, my mother attempted to placate me by saying: “Well no one reads the New York Times anyway.”

When my mother’s cancer returned, I promised to edit her book. And as her health grew worse, I suggested we publish it. I should have done this work earlier, but daughters are often selfish and consider themselves busy. And I hadn’t quite realized how much the manuscript had progressed since I last saw it.

Reading the novel now, I am struck by the power of her voice, the deceptive simplicity of her details, the beauty of her observations, her pitch-perfect treatment of drama and humor, her ear for dialog, and her sense of pacing. This, I realized, is not just a book I should publish to please my mother. It’s a book that deserves to be published on its own merits. For years, my mother tried to shop around for agents, editors, looking for any help she could get. But a Midwestern writer without connections, a female writer in the later years of her life, has a hard time attracting much attention. One wonders how many other great books are lost due to the same.

My goal: For my mother to hold this book and read the words of those who have taken pleasure in it. My hope: for the book to find more readers, reminding them of a not so distant or strange way of life.

Thank you to the friends and writers who have read this book and offered their words of praise. Thanks to the tireless Northcrest staff for their excellent care of our mother. And thank you to my family, especially my brother David Hoover and sister Lisa Carstens, who have worked so hard to help our mother transition between living situations and doctor’s appointments. I’ve gotten the easy part, the more gratifying part, the part that returns our mother to her girlhood.

Thanks most of all to our mother for living this story and writing it so impeccably, with so much authenticity. Though knowing our mother, I can’t imagine her doing otherwise.